In the morning of summer, Judith could have almost been stopped in her tracks by the pure chill running through her veins as she was moving in the very apartment-museum of Akhmatova-Anna in St. Petersburg. The memorial hush of the corridors, the ghost-echo of wartime Leningrad, the polished floors reflecting light from the Neva had ferried her soul across continents and through decades. For Judith, this was not a stop that one would be happy to put down casually on an itinerary for cruises. The visit was a pilgrim act of love-a translator’s devotion come alive, a gift from the heart to a poet she had long revered.

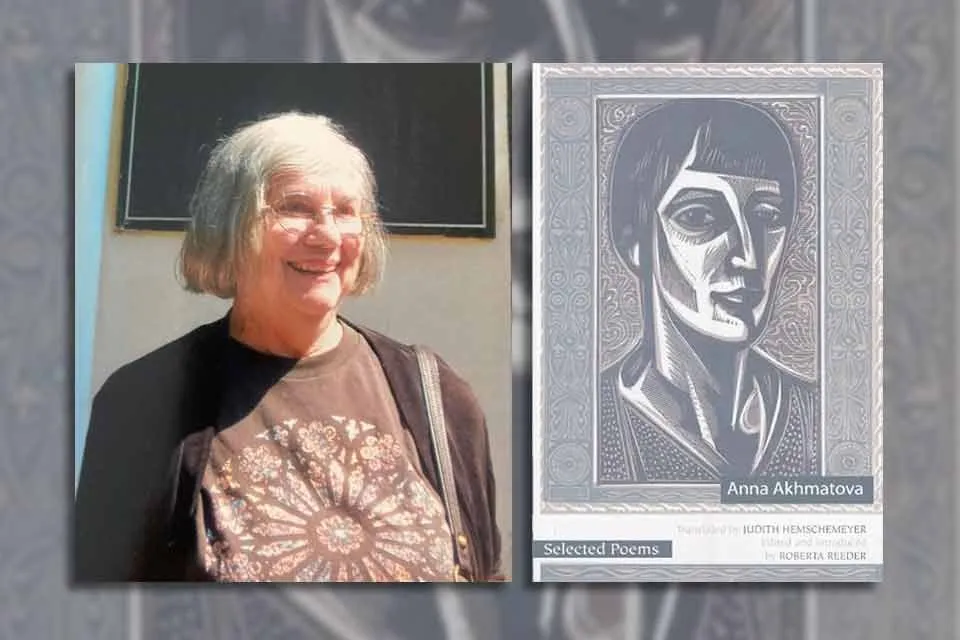

October 20th, 2025, witnessed the print of an obituary in World Literature Today: for Judith had passed away at ninety-three years, her journey being remembered as a “Pilgrimage and Passion Project”. Yet, the story runs far deeper than a mere headline, one that cuts across poetry and translation, self-education, travel, and unyielding fidelity to an artistic mission, unbounded by age, geography, or political limitations. The following would be an N. Y. Times-style feature on that journey, its inception, its stakes, its turning points, and the legacy Judith has left behind.

The spark in Wisconsin

Judith Hemschemeyer was born in Sheboygan, Wisconsin, and raised in a Midwestern town so far removed from the icy shores of the Baltic or Soviet corridors of intelligence. (Poets & Writers) In her reflection years later, she recalled having read some of Akhmatova’s poetry in translation in the early 1970s and being moved by their elegiac beauty and the very existence of that poetry despite censorship in Stalinist times. “I read a few of Anna Akhmatova’s poems in translation … and was so struck by one of them that I decided to learn Russian in order to read them all,” she stated.

The first block in the style of the second block: higher perplexity and burstiness.

The poet, who had already many titles to her name and collections, including Very Close & Very Slow (1975), The Ride Home (1987) (Poets & Writers), felt that meeting had awakened something else within her-there was a call to translate, from one world to another. Translations were not a mere exercise for her; they were, in fact, a form of devotion. Her words in the translator’s preface were as follows: “I became convinced that Akhmatova’s poems should be translated in their entirety, and by a woman poet, and that I was that person”.

From a punk adulteration into monumental translation

Learning Russian is no easy thing for the adult scholar-poet. Judith entered that world with the seriousness of a pilgrim walking toward a shrine. The period of the 1970s and 1980s was spent by her getting bearable from immersion into the language itself, history, and the buried lore of suppressed verse. Out of such travail issued the landmark translation: The Complete Poems of Anna Akhmatova (Zephyr Press, 1990), edited by Roberta Reeder. The volume itself, the more than 900 pages of its expanded edition, have been described as “a milestone.”

Her annotation and introduction did not shy away from the poet’s underground existence under the Soviet regime. She pointed to the underground manuscript copies, memorized lines, the burning of poems in ash-filled rooms, and the refusal to stop creating. Through the translator’s eyes, Akhmatova’s poems became more than literary texts – acts of survival, of testament, and of devotion.

For Judith this was not just biography; it was a mirror. Her own journey, from Middle America to Russia, from poet to translator, from scholar to pilgrim, mirrored the deeper journey of the poets she translated: from suppression to voice. Her work was an act of rescue: of poems, of a legacy, and of voices long silenced.

A Pilgrimage in Reality

Plenty of translations are done at a desk. Her entire project was mapped in the space. In June 2014 she took a Baltic cruise with friends and colleagues (including Kathleen Bell and composer Moya Henderson) that stopped in St. Petersburg. While there she had the privilege of touring the Akhmatova Museum (the apartment on the Fontanka where the poet lived and worked) with a guide all to herself. She walked the stairwells and corridors where the poet’s works were once whispered and burned away.

Eventually and lastly Judith reached the Akhmatova Museum, and she, full of giddiness, was like a pilgrim on sacred ground.

The time of translation was the time of the pilgrimage: the text disappeared into the being traveled, and scholarly worship became an embodied travel. She would restaurate the ashtray held by the museum and where the banned poem Requiem was memorized, she would touch the narrow shelf where Akhmatova’s son was under house arrest, and the weight of history would merge with that of present time.

This was more than sightseeing. It was paying homage. And it would change the entire career of hers-the translator as the pilgrim. The task of translation will be the way she takes not only to the text but to the actual meaning of that text-resistance, memory, survival.

Getting passion into publishing

The translation brought Judith recognition among literary circles. The Complete Poems of Anna Akhmatova was designated one of The New York Times Book Review’s “Best Books of the Year” upon its initial publication. Yet, beyond the honors, the project had effects on the field: issues of Russian-English translation, women translators in male-dominated fields of poetry, and politics of memory in literature.

In her essays and introductions, she did not hold back from activism. She insisted on the role of the “translator as poet” and argued that Akhmatova’s voice deserved not only fidelity of meaning but also fidelity to poetic cadence, faithfulness to the living pulse of the Russian language itself (writing.upenn.edu). Her editions are replete with biographical essays, historical chronologies, copious notes, and photographs, turning them into cultural artifacts themselves just as much as translations. For the readers of Akhmatova, Judith’s work opened hitherto inaccessible corridors.

Her own poetry went on through these years, reaching completion with Lovely How Lives (Snake Nation Press, 2010), the volume that wrote lines such as:

Lovely how lives of the great overlap

or just miss. Between Dickinson’s death

and Akhmatova’s birth—a three-year gap.

… But not the soul of this “seaside girl.”

In that sense, the pilgrim became the poet; the translator very much remained the creative voice; the journey very much remains ongoing.

The crossroads: age, travel and the creative life

Remarkably, Judith set upon this translation travail quite late in life and began the physical pilgrimage well into her late seventies. The combination of age and ambition is an under-reported subject in the stories of writers—but Judith’s journey is a reminder that passion need not wane with time. It grows, deepens, and sometimes requires a whole new terrain.

On the Baltic voyage, she emerged not merely as a senior literate, but as an explorer. The casinos and shows aboard the luxury liner had an air of the unfamiliar for her, but she kept her eyes on the prize-the museum, the texts that had been translated, the conversation going on between poet and translator. Thus she modeled another kind of pilgrimage: the pilgrimage of a late-life commitment, of creating renewal beyond given life milestones.

In one of her essays she spoke of the translator’s task as being faithful not just to the poet’s words but to the poet’s life, to the censor’s hammer, to the archive of resistance. To go to those places, to taste those artifacts, to bridge those linguistic frontiers. That is the pilgrimage.

Legacy and the gift of transmission

When Judith died, the literary world marked the loss very softly—but those who keep her legacy have set her translations on the shelf, in classes, in the hearts of those who read them. Her Akhmatova translation remains the standard for the scholars; her life path stands as the exemplar for how a translator can also be a poet. The pilgrimage, for those searching for meaning and faith, thus remains as much in their journey as in their destination.

One fellow-worker had written about Judith: Learning from her life must inspire others… to hold fast to the passion that animates true scholarship and creativity, passion that refuses to be dampened by age or circumstance. (World Literature Today) Indeed, Judith’s gift is to reflect the translator as a pilgrim, the poem as a route, and the life of ideas as a journey.

A former student recalls: “When I asked her how she learned Russian at the age of fifty, she smiled and said matter-of-factly, ‘I had to walk there.'” The words lingered: She walked toward language, toward history, toward a poet who refused silence—and in doing so, she walked toward her own vocation.

Judith Hemschemeyer’s story resists the prevailing notion in the literary landscape where swiftness triumphs over depth and viral succeeds slow study. It reminds how translation is not an act of mechanization but of pilgrimage. It reminds us how the creative life is not confined to early spurts but can flower in later decades. It reminds us how fidelity—to language, to voice, to memory – is truly radical in the current cacophony.

For writers, translators, readers, and seekers of meaning: this is an atlas. This map says that to pick up a poem in translation is to set out along a journey. To journey toward the literary-geographic and historical source of that poem redresses fragmentation. To put that translation to press is to share a sacred ground with others.

Hence we think of Judith Hemschemeyer: not solely as a translator, as a poet but as one who has found herself on a pilgrimage. Her journey beckons us to find ours.

A last image

Picture her in the museum in St. Petersburg: little rays of daylight filtering through a narrow window; the shelf where the poet’s son had been asleep those few days; the ashtray into whose forbidden lines memory was burnt; Judith standing quietly there, brushing her fingers over the register, barely making any sound with her footsteps on the floor. The journey is not over, she might say. The poems are still alive. The pilgrimage still goes on-from every reader who turns those pages to every translator who dares to walk the distance.